More than a decade ago, Alzheimer’s vaccines appeared in clinical trials — but failed. Now several companies are gearing up to test the next generation of preventive treatments.

In the early 2000s, doctors and scientists were cautiously optimistic about a novel approach for treating Alzheimer’s disease. Rather than developing a pill that people would need to remember to take every day or antibodies that would need to be infused every few weeks, they began testing vaccines against the beta-amyloid protein, which forms plaques and aggregates in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

What seemed like an elegant solution proved to be a quagmire. In 2002, Elan Pharmaceuticals shut down its Phase 2 trial of its Alzheimer’s vaccine because patients’ immune systems began developing antibodies that attacked healthy cells, causing severe cases of brain swelling. Other attempts at vaccines either failed to generate an immune response or caused too many side effects.

Since then, researchers have worked to refine the safety and effectiveness of Alzheimer’s vaccines. Andrea Pfeifer, CEO of AC Immune SA, which develops vaccines against Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease co-chaired a symposium on vaccines for neurodegenerative disease at the 2025 AD/PD conference in Vienna, discussing the vaccines in the pipeline.

“We are in a situation where we can actually generate a sustained, highly, well-controlled antibody response against the toxic target [amyloid and tau proteins],” Pfeifer told Being Patient. Vaccines, also called active immunotherapies, she said, would be more efficient at the population level because they’re cheaper, safer, and easier to access than anti-amyloid drugs.

How do Alzheimer’s vaccines work?

Vaccines are active immunotherapies, meaning they train the body’s immune system to recognize and respond to protein plaques and aggregates.

“Instead of giving the patients externally produced antibodies, we actually get the body to generate their own antibodies,” said Pfeifer.

The vaccines contain pieces of beta-amyloid, tau, alpha-synuclein, or other proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Rather than showing the immune system one piece of a protein, it presents multiple components, generating what immunologists call a “polyclonal response.”

When the body’s immune system encounters them, it remembers what the different pieces of these proteins look like and develops multiple antibodies against them, which, Pfeifer said, generates a “broader immune response” with a “much bigger impact on the toxic proteins which you want to eliminate.”

For Alzheimer’s disease, Pfeifer said it might take three or four injections to teach the immune system to recognize these proteins. Afterward, patients would only need to see a doctor once or twice a year for a booster shot.

How vaccines are different from anti-amyloid drugs

In contrast to vaccines, anti-amyloid drugs are passive immunotherapies. The infusions deliver pre-made antibodies that stick to specific forms of beta-amyloid, triggering their removal.

Leqembi and Kisunla require biweekly or monthly visits to an infusion clinic, which could mean traveling hours for those who live in rural areas. In contrast, going to the doctor once or twice a year is far more convenient and scalable, she explained.

What makes the new generation of Alzheimer’s vaccines different?

The first Alzheimer’s vaccine shut down its Phase 2 trial early. The vaccines caused people to develop antibodies that attacked healthy cells, leading to several cases of severe brain swelling.

The vaccines trained the body to recognize the entire beta-amyloid protein. Some of the immune cells could get confused by other healthy proteins in the body that might look similar to some small regions of beta-amyloid. This led to a non-specific response that caused a lot of damage. If the toxic forms of beta-amyloid are nails sticking out of the wall, then the early versions of these vaccines were trying to use a sledgehammer to nail them back in.

The newer vaccines are far more specific. So far, early trials of AC Immune SA’s vaccines suggest they’re much safer, don’t cause severe brain swelling, and are better at teaching the body’s immune system to target beta-amyloid and tau proteins. Rather than a sledgehammer, these vaccines are smaller and more precise — they can get the job done without causing extra damage.

Could Alzheimer’s vaccines treat or prevent Alzheimer’s disease?

Like many other treatments in development, Alzheimer’s vaccines take aim at the earliest stages of the disease or preventing it altogether.

“The whole field is moving away from late stage treatment,” said Pfeifer. “If you have heavy symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease, your brain has 20 to 30 percent of brain cells left.” At that stage, any treatment effects are bound to be small.

While blood biomarkers, cerebrospinal fluid tests, and PET scans can spot if someone has beta-amyloid or tau pathology in the brain, they aren’t perfect at predicting whether a person will remain asymptomatic or progress.

Vaccines in active trials

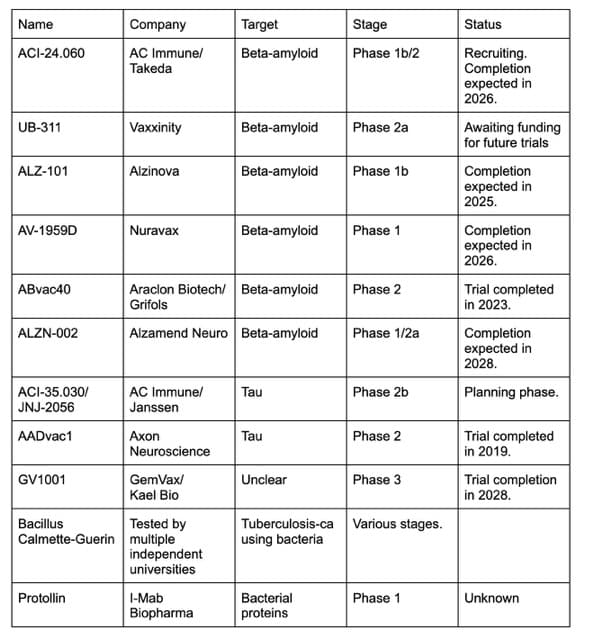

As of AD/PD 2025, there are at least 11 vaccines active in human clinical trials:

AC Immune SA, in partnership with Takeda, is testing an amyloid-targeting vaccine called ACI-24.060 to see if it could prevent Alzheimer’s disease in people with Down syndrome. As many as 90 percent of people with Down syndrome develop an early-onset form of the disease. The results of the trial are expected to be available in 2026.

In conjunction with Jannsen, AC Immune SA is planning a Phase 2 study of 498 people to test whether its tau vaccine, JNJ-2056, could prevent cognitively healthy people with Alzheimer’s biomarkers from developing the disease. The trial will track people over four years, and if successful, Pfeifer thinks it could garner accelerated approval from American regulators. However, it may take a while to recruit enough patients for the trial, and we won’t know if it works for another several years.

Pfeifer is optimistic about Alzheimer’s vaccines and their potential as a cheap, scalable, and convenient treatment that may one day prove to prevent the disease by targeting beta-amyloid, tau, and other protein aggregates in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. As the world’s population continues to age and the number of people with dementia is set to increase in the coming decades, effective vaccines may be hitting their stride just in time.

“We are looking at the biomarkers, identifying the people at risk, and then we treat them according to what protein they have [built up] in the brain,” said Pfeifer. “We call this precision prevention.”