The DIAN primary prevention trial is testing whether an anti-amyloid drug can prevent Alzheimer’s in people who are genetically predisposed — but don’t yet have symptoms. NIH changes mean its current funding sources are on the line.

A person who struggles with tasks they’ve been doing for years or asks the same question over and over again may be showing the first outward symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. But long-term studies — like those carried out by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network (DIAN) — have shown that changes inside the brain can start many years, even decades, before these early symptoms ever appear. If these brain changes are happening so early on, could the key to an Alzheimer’s cure be to get way, way ahead of symptoms, and treat the disease when it’s still outwardly invisible? Researchers are now exploring whether a new generation of Alzheimer’s monoclonal antibody drugs — originally designed for people in the disease’s early symptomatic stages — could be even more effective in people who are still years away from developing Alzheimer’s symptoms.

To test this idea, DIAN scientists have recruited young people who carry genetic mutations that virtually guarantee the development of Alzheimer’s later in life. Those participants are now part of the DIAN primary prevention study, which explores ways to catch Alzheimer’s earlier and keep amyloid plaques from ever forming. They’re receiving the experimental Alzheimer’s antibody remternetug, and the researchers will track changes in their brains over time to understand whether this anti-amyloid drug could stop Alzheimer’s symptoms before they appear.

Choosing the right drug target

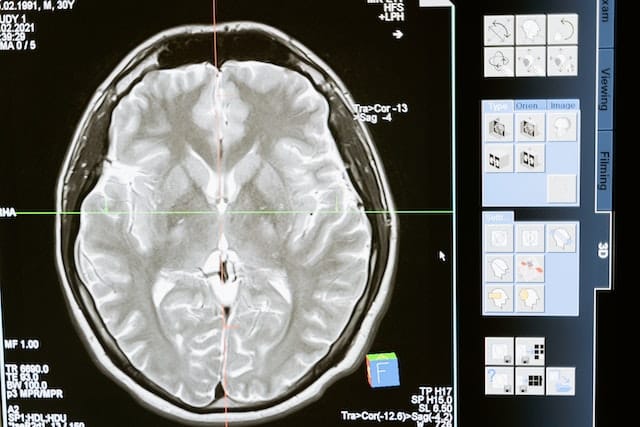

The experience of Alzheimer’s varies from person to person, but all cases involve these three changes in the brain: beta-amyloid plaques, tau protein tangles, and neuroinflammation. According to Michael Weiner, a radiologist at the University of California San Francisco who helped design the ADNI studies, Alzheimer’s starts “when amyloid plaques are detectable in the brain.” Doctors look for these signs using diagnostic tools like PET brain scans and Alzheimer’s biomarker blood tests.

Anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody drugs for Alzheimer’s have just started to hit the market in the last couple years. This new class of drugs is the first ever Alzheimer’s treatment approved to actually modify the disease pathology in the brain, as opposed to just putting a band-aid on Alzheimer’s symptoms. These drugs — approved for people in the earliest stages of symptomatic Alzheimer’s — work by clearing beta-amyloid plaques from the brain.

Everyone has beta-amyloid proteins, but changes in the way this protein is processed cause it to form abnormal plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s.

“Something happens around the time that early plaques develop,” said Eric McDade, a neurologist at Washington University in St. Louis who is leading DIAN’s new primary prevention study.

Weiner, McDade, and other researchers are still working out precisely what that is. Evidence suggests that the faulty amyloid proteins that ultimately clump into plaques are, themselves, toxic to neurons and could be the key driver of neurodegeneration. However, researchers have also considered the idea that the excessive immune response these proteins elicit could play a major role in the disease. Or, misfolded beta-amyloid proteins could just initiate changes in the other major Alzheimer’s-associated protein: tau.

Like beta-amyloid, strands of tau protein are present in everyone’s brain, but problems occur when they get tangled. Tau tangles form after amyloid plaques. These tangles are “associated much more closely than the plaques with clinical symptoms that we recognize as Alzheimer’s disease,” McDade explained.

DIAN scientists are currently conducting a separate, secondary prevention study in which participants who have already developed both amyloid plaques and tau tangles are receiving regular infusions of Eisai’s experimental anti-tau drug E2814.

The DIAN team plans to test other tau-targeted medications, too, but as of now, they are still evaluating anti-tau drug candidates. As Weiner at UCSF wrote to Being Patient: “There is a lot of interest in blocking production or clearing tau, but we are in a very, very early stage.”

When to target amyloid

While anti-tau medications may be the next wave of Alzheimer’s treatments, researchers have been working on amyloid-targeted medications for a much longer time. In fact, it’s been a quarter century since the first Alzheimer’s monoclonal anti-amyloid antibody (mab drug) entered clinical trials.

According to Weiner, the earliest anti-amyloid mab drugs for Alzheimer’s didn’t quite succeed at clearing amyloid plaques. But this newer generation seemed to crack the code, effectively reducing amyloid plaques and slowing the progression of cognitive decline.

While critics argue that a slight slowdown in cognitive decline is not enough to warrant the cost and side-effects of the mabs that are currently on the market, researchers and pharmaceutical companies continue to tinker with them. The DIAN team has found some evidence to make them optimistic that earlier administration is the answer. For example, in a previous secondary prevention study conducted by DIAN, Roche’s experimental antibody gantenerumab reduced amyloid plaques in people who were not yet experiencing clinical symptoms. Roche discontinued gantenerumab when the drug failed to slow cognitive decline in a Phase 3 clinical trial. Would it have been successful if it had focused less on improving outcomes for people already showing early signs of Alzheimer’s and more on preventing disease onset? That’s a question the DIAN team is now probing with remternetug.

Why remternetug?

McDade said his team chose the experimental anti-amyloid remternetug over FDA-approved medications like Leqembi and Kisunla in part because it can be administered via a quick injection, unlike Leqembi and Kisunla, which require time-consuming, intravenous infusions.

It was also an intriguing prospect, McDade said, because it has shown to be very effective at binding to amyloid plaques in the brain. In fact, early results from a separate Eli Lilly Phase 3 clinical trial — one enrolling participants with early-stage, symptomatic Alzheimer’s — provides evidence that it may be clearing out these plaques in about a third of the time of its Lilly predecessor, Kisunla.

Even though Eli Lilly does not have data demonstrating remternetug’s ability to slow cognitive decline before the start of the DIAN primary prevention trial, McDade said, “the drug at least is engaging what it’s supposed to.”

With that piece of uncertainty removed, McDade feels more confident that the trial he is leading and Eli Lilly’s clinical trial are actually testing whether targeting amyloid is an effective strategy for treating or preventing Alzheimer’s.

If so, then he looks forward to seeing a redoubled effort to develop new, less expensive treatment options that can target toxic amyloid proteins. In the future, he hopes that monoclonal antibodies will be just one of many drugs available for the treatment and prevention of Alzheimer’s. “We would all like to move beyond the point where using these immunotherapies is the only thing that we have,” said McDade.

What’s next for the DIAN primary prevention study?

It’s unlikely that any one medication will turn out to be a “silver bullet” cure for every person at every stage of Alzheimer’s. That’s why researchers at DIAN and elsewhere are simultaneously exploring a variety of experimental medications and strategies for preventing, slowing, or treating the disease.

Weiner thinks this multi-pronged approach is essential. “We need to explore all options” for treating Alzheimer’s, Weiner wrote — amyloid therapies, tau therapies, and beyond.

Pursuing any option — let alone all the options — requires money. When DIAN launched the primary prevention study, the researchers planned to draw most of their funds from the NIH and Eli Lilly. Now, recent changes at the agency have called the DIAN trial’s continuation of federal funding into question.

McDade told Being Patient that the NIH has pushed off reviewing its grant for the primary prevention study and that the funds could be forfeited if the agency does not make a decision by May. “It’s interesting times right now,” he said. “Fortunately, we have been raising philanthropic funds and have funds from our pharmaceutical partner, Eli Lilly, that can sustain the trial for now,” he added in an email.

McDade cannot predict what will happen with funding, but he made clear that he and the rest of DIAN will continue doing what they can to improve the lives of people with Alzheimer’s. “Our mission remains the same and our commitment to the families involved in these studies is unwavering,” he wrote.

Andrew Saintsing (@AndrewSaintsing) earned a PhD in biology, and now he writes about science for outlets like Drug Discovery News.