Patient-founded nonprofit Voices of Alzheimer’s created a bill of rights for people living with Alzheimer’s. The authors hope it will change U.S. policymaking in a monumental way.

Now, there is a bill of rights for people living with Alzheimer’s disease. It was drafted by the patient-founded nonprofit organization Voices of Alzheimer’s.

“We really needed to issue a new document, one that we consider a living document. We’re not going to put it in the ground and leave it,” VoA president and CEO Jim Taylor said. “We hope every year to reexamine it and to re-publicize it, but also to make the changes that are important, given the advances that have occurred.”

Taylor and his wife Geri Taylor, who was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, later confirmed by doctors to be Alzheimer’s disease, have committed to living their lives “fully and passionately” despite Geri’s diagnosis.

VoA’s bill of rights is an extension of this commitment, Jim says — and it aims to ensure that people living with Alzheimer’s receive not only ethical treatment, but an equal quality of life.

Below, find the bill of rights — and a Q&A with Jim Taylor about the change he hopes it will inspire.

A Bill of Rights for People Living with Alzheimer’s

- We have the right to always be treated with dignity and respect

- We have a right to be free from discrimination in all forms

- We have the right to be diagnosed and treated promptly

- We have the right to annual cognitive screenings using the most effective tools in detecting and diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders

- We have the right to affordable, expeditious Medicare and other payer coverage for the full range of screening, diagnostic, and treatment options validated and approved by the FDA for Alzheimer’s disease including but not limited to cognitive screening, diagnostics, genetic counseling, and access to new biologic therapies, whether via infusions or self-injections.

- We have the right, in the case of Younger Onset Alzheimer’s, to access the same treatment and care as any person with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to Alzheimer’s disease and related cognitive illnesses covered by Medicare

- We have the right to participate in clinical trials without facing unnecessary barriers, and the right to treatments that have undergone rigorous testing in diverse populations

- We have the right to receive complete information about our diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, access to our medical information, and to be included in decisions about our care to the fullest extent possible

- We have a right to continuity in care, and continued care for non-Alzheimer’s disease health issues, across all stages of the disease

- We have the right to receive quality care in all medical settings from professionals trained in interacting with and caring for people living with cognitive impairment

Q&A with Jim Taylor

Being Patient: What motivated you to found Voices of Alzheimer’s?

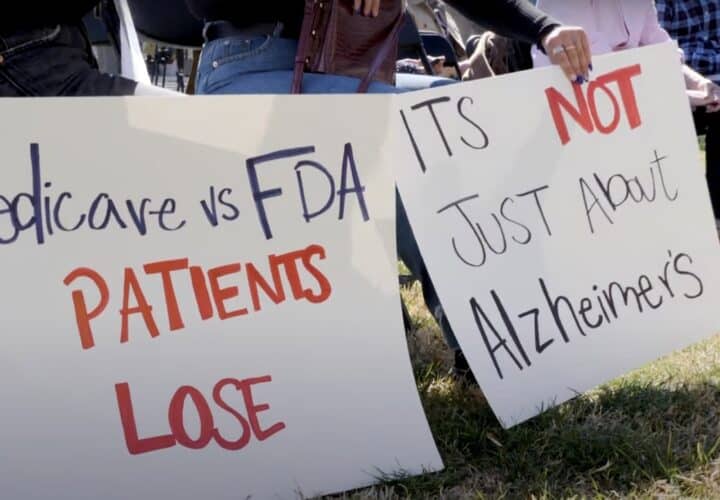

Taylor: A couple of years ago, the first disease modifying therapy for Alzheimer’s, Aducanumab, was approved on an accelerated basis. Aducanumab was not covered for the population by Medicare. You had to be in a state where they would only cover people in a clinical trial, which was outrageous. So we really began to organize and to speak out and to criticize the CMS, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, about how they are not covering therapies that they cover for all other disease areas.

We believe they’ve had a long history of discriminating against people with Alzheimer’s. So in order to do that, effectively, we created an organization called Voices of Alzheimer’s, which we launched in September of 2022, really as a vehicle to raise the voices of people living with the disease, their care partners and their friends to really become a chorus about what it’s like to live with the disease and why these revolutionary new drugs, diagnostics and therapeutics need to be approved rapidly by the FDA and covered by Medicare. So we felt that wasn’t happening to the degree that it should and that too many voices were not really being heard. We managed to do that with this new organization.

“I hope that over time, we will be able to introduce this document to our friends, regulators, and champions on the Hill so that they have a better understanding of what we experience on a day-to-day basis.”

Being Patient: I’d love to hear about the bill of rights published recently by Voices of Alzheimer’s. Can you tell me about the process of authoring it, who helped you and how that process began?

Taylor: It was a really interesting process. As we [members of VoA] came together we kept hearing a number of situations of problems that were repetitive and experiences that had happened to us individually. For example, once our general practitioner knew that Geri [Jim Taylor’s wife] had dementia and I started going to her appointments with her, the doctor would talk to me and not look at Geri. Seeing this in the medical profession was kind of surprising.

One time when Jerry was taken to the hospital in an ambulance, I was not able to enter with her through that entrance of the hospital. I got to her room 20 minutes later, and found that she was hysterical with three aids trying to get her into a hospital gown. And so I calmed her down, got her dressed, no problem. But she was terrified. She has dementia. So the next day I inquired and learned that none of the aides had had training with dementia. There are two hour courses online to introduce you and to teach you how to interact with a person with dementia. This should be a requirement for anybody in a medical setting, whether they’re receptionist or whether they’re a nurse or physician.

It will soon be the case that there may be a three or four year wait for a new patient to see a neurologist. This is intolerable because we have an early stage treatment available, and yet if you are not able to get the prescription for three years, you may be too advanced to even qualify to receive the medication anymore. We wanted to speak against that and what we believe is an intolerable situation. 5 percent of people with Alzheimer’s are younger than 65. If you’re younger than 65 you don’t qualify for Medicare yet. So after you’re diagnosed, you have to wait two years before you can receive disability payment and Medicare coverage.

This is another point that we are going to work on to ask for an exception, that people with early onset, once diagnosed, be given automatic access to Medicare. People older than 65 who are enrolled in Medicare are entitled to an annual cognitive screening. Fewer than 30 percent of people report having had a cognitive screening when they had their annual physical. Primarily this is because our general practitioners today aren’t trained or capable at this point to administer cognitive screening. We need to change that and provide general practitioners with the training and the skills and the tools necessary so they can include annual cognitive screening, because early detection for us is critical.

It’s also shown that up to 23 percent of cognitive challenges that show up in screening are reversible. Vitamin deficiencies and other causes that general practitioners can deal with and these are the things they can discover early to help reverse that course for their patient. Most folks with Alzheimer’s are still not informed by their physician that they have dementia. 84 percent of people living with dementia and their care partners report experiencing stigma and discrimination.

When Aducanumab was first introduced it was priced at $56,000 a year. That is completely unaffordable. We believe that we have the right to reasonably-priced medications. So given that scenario, and that background, we thought we need to make a statement of what we believe are our entitlements, our rights. When we came together first and did our research we found that other bills of rights for Alzheimer’s or dementia had been created previously, but they were 10 and 15 years old. Because of all the tremendous developments in screening for blood biomarkers and in disease modifying therapies, this is a totally new landscape.

We really needed to issue a new document, one that we consider a living document. We’re not going to put it in the ground and leave it. We hope every year to reexamine it and to re-publicize it, but also to make the changes that are important, given the advances that have occurred and whether or not that makes us rethink some of the way that our verbiage is written.

“There’s a willingness to help once we help them understand what the situation is.”

A lot of the projects that we are involved in and building on will be based upon the bill of rights and it’ll help people understand why we’re trying to educate and provide tools for general practitioners because we need them involved in brain health. We need them to do annual cognitive screening.

Being Patient: What is the overall impact that you hope the bill of rights will have on legislators?

Taylor: I hope that over time, we will be able to introduce this document to our friends, regulators, and champions on the Hill so that they have a better understanding of what we experience on a day-to-day basis. I think what we’ve found is anybody who’s touched by this disease, who understands what our needs are, there’s a bipartisan response to that. There’s a willingness to help once we help them understand what the situation is. The fact that 84 percent of folks still encounter stigma – that needs to be publicized, that needs to be known. We want our champions to be able to understand that and to use that in convincing their fellow congressmen and congresswomen to pass the bills that we need.

Being Patient: When thinking of clinical trials and the lack of diversity of participants, how do you hope the bill will impact clinical trial centers and potentially change the participation process?

Taylor: Anything we can do to publicize this crisis, as you know, is critical. One of the big inhibitors to more people in participating in trials is that they don’t learn about them. Many neurologists don’t ever mention participation in clinical trials to their patients. But with cancer patients, it’s very common practice. If there’s an appropriate trial for you to participate in, the physician or the office of the physician should inform the patient about that trial, encourage them to participate or to consider participation. Everybody has to make their own decision, and all of these drugs have some side effects and some issues that we all need to think through. But it’s very important that we be informed.

The diversity issue is a tremendously complex question. You know, that the drugs that have already been approved have very poor representation, particularly by the African American community and somewhat by the Hispanic community, and these two communities develop dementia at a much greater rate than white people. They need to be over-represented as a percent of the population in these trials, and yet we don’t come even close to having them represented as their percentage of the population. And there’s a lot of reasons for that, but primarily, we have a history of abuse. When thinking of Tuskegee, Henrietta Lacks – we have used African Americans in clinical trials in a way that is despicable on our history as a nation, as a research organization, and we must reinstill trust in these communities. And we have to do that by earning their trust, and going out and listening to what their challenges are.

Being Patient: What response so far have you received about the bill of rights?

Taylor: The response so far has been very positive. I got to present it to a large group of other Alzheimer’s organizations and dementia organizations and got a lot of compliments. A lot of people were asking, “Why didn’t we have this earlier?” Very quickly people were identifying the need and the ability to collaborate on something like this.

“What we’ve found is anybody who’s touched by this disease, who understands what our needs are, there’s a bipartisan response to that.”

Being Patient: What advice do you have for someone who has a spouse living with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia and navigating that diagnosis and journey with them?

Taylor: Frequently the advice to newly diagnosed individuals is to get your affairs in order. I think that’s helpful, but there’s no urgency in my opinion. It’s much more urgent to take the time to reflect on what your new life is. How do I integrate this unwanted new diagnosis into my vision of what the rest of my life is like? And that takes time. It takes pain. It takes perseverance and we all have to come to grips with that in our own way. My way was much different from my wife’s way, but before we could really go forward, we had to do that. And so I encourage people to take their time. I think a year is sufficient. If it drags on after that, then perhaps professional help is needed. But it took me really six to 12 months. It was a very, very hard and unwanted event in our life.

“For me, being a care partner has been a real opportunity for personal growth. I was never patient. I was never that kind. I was never that flexible. I always wanted to be right. Now a lot of those things aren’t very important anymore.”

My message for care partners: I always say that all we hear about is the burden of taking care of someone else. And I’ve been a care partner for 12 years and it has not been that hard of a lift. The early years, the longest part of the journey, is really not that difficult to be a care partner. Yes, the late stage of the disease is very difficult, both for the person with the disease and the care partner. There’s no denying that. But the whole journey is not difficult.

The second thing is we don’t balance that burden by looking at the opportunities. For me, being a care partner has been a real opportunity for personal growth. I was never patient. I was never that kind. I was never that flexible. I always wanted to be right. Now a lot of those things aren’t very important anymore. It really made me find out and understand, “What’s really important? For me, what’s really important in my relationship with a woman that I dearly love?” I look back and think about myself before and often wish I’d had a lot of these lessons a lot earlier in my life.

The other thing is that our goal as care partners really should be to promote the very best quality of life possible for the person we’re taking care of. And so much of that can come from our attitude. If I come in cranky and disagreeable most of the time, think about how that influences the person we’re taking care of. Not good. Yeah, they’ve got so many of their own challenges. We need to continually be on the sunny side, really bringing humor and happiness and warmth to the person we’re taking care of.

The final thing I would say to a care partner, and maybe the most important thing, is to practice self-care. We can’t take care of the person who we love and who has dementia if we don’t take care of ourselves first. And research shows that people who are caregivers have higher rates of cancer, heart disease and other diseases than their peers who are not care partners. So I encourage care partners: don’t cancel that doctor’s appointment. Don’t miss your annual physical. Eat well, exercise, make time for yourself. I don’t always do what I preach, but I try to and it’s very important.

As one diagnosed with dementia/ALZ in 2018, I have been educating myself and family on this disease. Yet, I feel trapped in not getting the treatments that are possible for me. Recently I came across Voices of ALZ. Your audio of this article has helped me to discover other possibilities. I now have two new resources to aid me through this journey. Thank you.

My husband is the later stages of Alzheimer’s Dementia now. Almost 3 years ago he was in a Clinical Trial…was in the early stages (mild) Alzheimer’s stage..the drug was Donanamab…Eli Lilly…after only 2 infusions he had severe Aria-E. Ended up in the hospital 1 month, had plasmaphoresis, in a coma 1 week, on seizure Rx over 6 months…severe verbal aphasia, couldnt walk..had a Tramatic Brain Injury…all that glitters in NOT gold… never went back to his former self !!! Lost I would say 4-5 years of his life.They were not transparent about the risks. Be more educated about drug RX..Who knew!!!!

How narrowminded and backward looking it is to devise rights for Alzheimer’s instead of Dementia which includes Alzheimer’s but a number of other dementing diseases and disorders. I am a medical professional and family caregiver with decades of experience with dementias. Please reconsider and include all dementia sufferers. Thank you.

Important points are made here, Sue! We’re big fans of Voices of Alzheimer’s, an advocacy organization founded and run by people living with Alzheimer’s. This is a great effort they made to create this landmark bill of rights and while they didn’t want to presume to speak for all people with all different forms of dementia — which can affect the brain in different ways — we hope the broader community follows suit. Thanks for reading.